The Art of Poetry in English: Origins, Masters, and Creative Techniques

Poetry has long been a vessel for human expression, weaving emotions, stories, and ideas into rhythmic and evocative language. From ancient epics to modern free verse, English poetry spans centuries, cultures, and styles. Understanding its origins, notable poets, and techniques can deepen appreciation and inspire new creations.

The Roots of English Poetry

English poetry traces its lineage to Old English traditions, with Beowulf standing as one of the earliest surviving works. Composed between the 8th and 11th centuries, this epic poem reflects Germanic heroic ideals. The Middle Ages introduced structured forms like the ballad and sonnet, while the Renaissance saw poets like William Shakespeare refine these techniques.

The Romantic era (late 18th to early 19th century) shifted focus to nature, emotion, and individualism, with William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and John Keats leading the movement. Modern poetry, from T.S. Eliot to Maya Angelou, embraces experimentation, breaking traditional rules to explore new voices and themes.

Influential Poets and Their Legacies

-

William Shakespeare (1564–1616)

Best known for his plays, Shakespeare also crafted 154 sonnets. His works, such as Sonnet 18 ("Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?"), explore love, beauty, and mortality with precise meter and metaphor. -

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

A recluse who wrote nearly 1,800 poems, Dickinson’s unconventional punctuation and slant rhymes challenged norms. Her themes of death, nature, and the self remain influential. -

Robert Frost (1874–1963)

Frost’s accessible yet profound verse, like The Road Not Taken, uses rural imagery to ponder life’s choices. His mastery of blank verse and colloquial speech made him a defining American poet. -

Maya Angelou (1928–2014)

A civil rights activist and memoirist, Angelou’s Still I Rise celebrates resilience and identity. Her rhythmic, lyrical style blends personal and universal struggles.

Crafting Poetry: Techniques and Forms

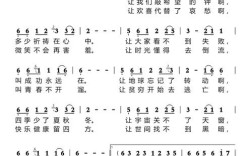

Rhyme and Meter

Rhyme schemes (e.g., ABAB, AABB) and meter (e.g., iambic pentameter) create musicality. Shakespearean sonnets follow ABABCDCDEFEFGG, while free verse abandons strict rules for organic flow.

Imagery and Symbolism

Vivid descriptions engage the senses. In Daffodils, Wordsworth paints "a host of golden daffodils" to evoke joy. Symbols, like Frost’s "road," represent broader concepts.

Metaphor and Simile

Metaphors directly compare unlike things ("Hope is the thing with feathers"), while similes use "like" or "as" ("My love is like a red, red rose").

Repetition and Alliteration

Repetition emphasizes key ideas, as in Angelou’s Phenomenal Woman: "I’m a woman / Phenomenally." Alliteration (repeating consonant sounds) adds rhythm, like Poe’s "weak and weary."

How to Read and Write Poetry

Reading Poetry

- Read aloud to hear rhythm and tone.

- Analyze structure: Note line breaks, stanzas, and punctuation.

- Interpret themes: Consider historical and personal context.

Writing Poetry

- Choose a form: Start with haiku (5-7-5 syllables) or free verse.

- Brainstorm imagery: Use concrete details over abstractions.

- Revise for impact: Trim excess words; refine metaphors.

Poetry thrives on creativity and precision. Whether reading classics or composing original lines, engaging with verse enriches language and thought. The best poems resonate across time, offering insight, solace, and beauty—proof that words, carefully chosen, can shape worlds.